- Home

- Connie Haham

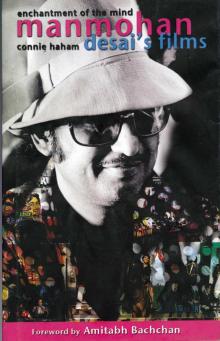

Manmohan Desai's Enchantment of the Mind

Manmohan Desai's Enchantment of the Mind Read online

About the book

Anhonee ko honee karna hamara kaam hai.'(It is our job to make the impossible possible.) The sentence leading into the title song of the blockbuster film Amar Akbar Anthony sums up the magic of Manmohan Desai, the master entertainer whose desire to please his public made his name synonymous with success during much of his career in popular Hindi cinema from 1960 to 1988. In Enchantment of the Mind: Manmohan Desai's Films, Connie Haham delves into the director's work and analyses some of his cinematic signatures - speed, fun, adventure and delight, alongside a devotion to motherhood and a stance in favour of inter-religious harmony. His cinema is fondly remembered for its many catchy tunes and the characters brought to life by leading stars, from Raj Kapoor to Amitabh Bachchan. Lending extra magic to this book is Manmohan Desai's own account of a life dedicated to cinema - a medium he wielded artfully to depict both struggle and an affirmation of life.

About the author

Connie Haham encountered Indian cinema in Paris in 1979. Since then, she has written on Hindi popular cinema for magazines and newspapers in India, France and the United States. Fascinated by Manmohan Desai's films, she decided in the early 1980s to get to the root of their ever-lasting appeal. In 1985, when the Pesaro Film Festival in Italy showcased Indian cinema, she was invited to speak on Manmohan Desai. In 1987, she was a consultant for the Miracle Man, a programme that appeared in the Movie Mahal series, directed by Nasreen Munni Kabir for Channel 4 in Great Britain. Haham has also written and spoken on the dialogues of the writing team Salim-Javed. She has taught English as a foreign language in Paris, France and Austin, Texas. Currently she divides her time between Paris and Austin, with regular dips into the enchanting world of Hindi cinema.

ROLI BOOKS

This digital edition published in 2014

First published in 2006 by

The Lotus Collection

An Imprint of Roli Books Pvt. Ltd

M-75, Greater Kailash- II Market

New Delhi 110 048

Phone: ++91 (011) 40682000

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.rolibooks.com

Copyright © Connie Haham, 2006

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, print reproduction, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Roli Books. Any unauthorized distribution of this e-book may be considered a direct infringement of copyright and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Cover Design: Aarti Subramanium

eISBN: 978-93-5194-049-4

All rights reserved.

This e-book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form or cover other than that in which it is published.

enchantment of the mind

manmohan

desai’s films

contents

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Preface

manmohan desai

The Filmmaker, The Man

two films in close-up

Amar Akbar Anthony

Coolie

a wide angle on manmohan desai’s work

Kaleidoscope

Kinetics

Technical Choices

The Players

The Child

Comedy

Serious Undertones

Reality

Women

The Manmohan Desai Legacy

Endnotes

Filmography

Bibliography

foreword

Clearly, the re-assessment and insightful commentary on Manmohan Desai was long overdue. After all, his films stemmed from a concern with the way people live together and how this co-existence could perhaps even come close to a state of utopia. At the heart of Manmohan Desai’s immense oeuvre was an affirmation and celebration of struggle.

Manji, as he was called by those who loved and admired him, would perhaps balk at any cerebral analysis or research about his films. Without knowing it—like all great masters—effortlessly he had posited significant sub-texts into his hyper-fantasies, which to the superficial eye seemed like fleeting, will-o’-the-wisp entertainers.

Somewhere within, he was quite prescient about the fact that his films, as a collective whole, would be ultimately accorded their just estimation by the critics, thinkers and academicians. ‘Laugh at me today,’ he would tell his detractors good-naturedly, ‘but mark my words, you’ll appreciate my work some day, even if it’s too late.’

It’s never too late. Indeed it’s a matter of personal pride for me that at long last, Manmohan Desai has been given his richly deserved stature in the pantheon of film greats.

In film after film, he had set his own rules of right conduct, a fierce sense of loyalty towards fellow-beings and above all, a deep veneration of the mother figure. At a time, around the 1970s, when families all over the world were splintering and it had become fashionable for young people to go independent, he insisted that parents came above God and of course, above self. Hurt them and you hurt yourself, was his simple, oft-repeated credo which continues to echo in the techno-savvy cinema of today.

Needless to say, Manji has been frequently imitated but never quite equalled. Not by a long shot. Because part of the distinctive drive and brio of his work came from his instinctive belief that films are a temporal as well as a spatial medium. He loved flamboyant colour, costume, and décor, but he never allowed these elements to freeze into static compositions. A genius of changing patterns and complex movements, he filled his pictures with swooping crane shots, voluptuous displays of story telling, dance-music-action, superbly colloquial dialogue and spontaneously orchestrated background detailing.

Stylistically and thematically, Manmohan Desai’s films might be described as ‘fantasticated’ expressions of romantic idealism. In fact, love, honour, separation, vindication and reunion were his abiding obsessions. While recounting those deceptively believe-it-or-not stories, he retained that key element of wonderment. He was akin to a child who had lost himself in a fairground, had clambered onto a Ferris wheel and could have enjoyed the ride till kingdom come. He never betrayed the slightest sign of exhaustion; he continued to be an irrepressible ranconteur even when a chronic backache confined him to a hardboard chair.

The diverse personalities of the dramatic director and the extravagant producer coalesced in Manji. His films generally took place in scenic outdoor locations or in studio-manufactured settings, where the boundaries between fantasy and everyday life could be transgressed.

Maybe it was the shortsightedness of the film commentators of the time that drew the simplistic comment that his work was absurd, far-fetched, incredible and unreal. Compared to the inter-planetary adventures of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, Manmohan Desai’s foreverland was as familiar and as authentic as the people living next door. ‘See, people praise Spielberg’s imagination but have problems with mine,’ he would declare with bemusement.

Rationalists quibbled but audiences adored him. They wanted more. The criticism that Manji belted out films which were so fast, furious and funky that the viewers were not allowed any time to think, just doesn’t hold any water today. The fact is that several of his films—Sachaa Jhutha, Aa Gale Lag Jaa, Amar Akbar Anthony, Naseeb and Coolie to name a few—have achieved cult status, constantly inviting thought, discussion, and most hearteningly, hosannas of approval.

Any list of films which have advocated secularism is now topp

ed by Amar Akbar Anthony. When it was released, its full-throttle message of communal harmony wasn’t perceived, but it is acknowledged unconditionally today. True to his nature, Manmohan Desai never spoke about his films’ agenda because he didn’t have to.

Stories came to him naturally, inspired infallibly by the conditions and people around him. Anthony was a drunken lout he had encountered oftentimes in the back alleys of Khetwadi, a cramped city area where Manmohan Desai felt completely at home. No wonder, he retreated back to the congestion and the crowds after shifting for a short while to the upscale Malabar Hill.

To know Manmohan Desai was to know a man of compassion. Despite the tremendous success of his films, his feet never left the ground. His screenplays often germinated from major and minor incidents, which he may have read in the newspapers or heard about from his neighbourhood gully cricket pals. He belonged to an era when the director was an auteur, imprinting a firm signature on every frame of his films. And his signature was of a spry wizard who coaxed the audience towards a wild and improbable realm, and yet remained strongly rooted in the soil. A paradox yes, but a splendid, unparalleled one.

The story ideas of Amar Akbar Anthony and Coolie were inspired by real life. If they seemed like fantasies, it was because his USP was to make the tough reality palatable, underscored by optimism. His valorous protagonists did not die in his films; they lived even after they had been riddled with bullets. The most obvious example of this was the recovery of the eponymous Coolie, attacked by gunfire at the Haji Ali durgah. Miraculously, in real life too, I survived a serious physical injury on the sets of the same film. His concern and prayers were always with me, as they were indeed with all the actors and technical crew whom he treated as an extended family.

Whether it was at a music sitting, a script brainstorm or a shooting schedule, Manji was the livewire. His enthusiasm and self-belief were immediately infectious. Nothing was impossible for him to conceive and execute, from a helicopter flight over the London skyline, a shootout in a revolving restaurant or a chase atop a speeding train. He encouraged actors to delve deeper into themselves, and discover facets they didn’t know existed.

From my personal experience, I can say the drunken act, which I came to be associated with, was tossed off by him—in the snap of a finger just as the camera was about to roll. The soliloquy addressed to my mirror image is remembered to date for the hilarity that Manji invested in a sequence that everyone thought was unimaginable.

From his first film on, the black-and-white Chhalia, featuring the stalwarts Raj Kapoor and Nutan, it was evident that the young man in his 20s then, would redefine Hindi cinema. He did just that, unfazed by the fluctuating trends and fads right till Gungaa Jamunaa Saraswathi. Eventually he handed over the reins to his son Ketan, but there were still many more films that were ticking in his heart and mind. Everyone who knew him was convinced that he would be back in action, with renewed vigour.

Manji was full of surprises. He suddenly upped and decided to go, he left just as a fist disappears when we open our palm. He had the last laugh.

A study of his incalculable cinema was pending for decades. I am deeply grateful for the painstaking years that Connie Haham has spent on the book. Her dedication, understanding and appreciation of Manmohan Desai are palpable in every page and word.

The author has been one of the earliest and unwavering supporters of popular Indian cinema. With this book, she has contributed immeasurably in preserving the memory of the great director and the great man. A humanist who never said he was one.

Thank you Connie. On behalf of Manmohan Desai, myself and the undiminished legion of admirers of the Manji of real miracles.

acknowledgments

My thanks to Nasreen Munni Kabir for encouraging me to undertake this project, to Filmfare magazine for access to their archives, to critic Louis Marcorelles of Le Monde for his kind and repeated encouragement, to film critic Michel Ciment whose intellectual integrity and thoroughness during weekly radio debates have inspired me, to my husband and children for making the major adjustments necessary to allow me to spend a month researching in Bombay and also to Urvashi Butalia, P.K. Nair, Bikram Singh, Gul Anand, Edward H. Johnson, Prakash Pange, Uday Row Kavi and Rao Chelikani, and Johnana Clark, Helene Meyers, Keith Walters, Philip Lutgendorf, Henri Micciollo, Dipa Chaudhuri, and to all those who were good enough to grant me interviews.

preface

1March 2004 marked the tenth death anniversary of Manmohan Desai. A fall from the terrace of his Khetwadi home brought the 57-year-old filmmaker’s life to an end in the spring of 1994. The suspected suicide came as a shock both to those nearest to him and to the film world as a whole, as testified in countless articles and tributes in the Indian and international press in the month following his death. The articles that appeared spanned the gamut of reactions: praise for Desai as a man and as a filmmaker, heartfelt remembrances from those who had worked with him, indignation and disbelief over the circumstances of his death, and speculation over possible motives for suicide—depression over severe backaches being most frequently offered as an explanation.

At that time, I could not help feeling a personal sadness over his death. I had, after all, spent the better part of four years studying Manmohan Desai’s work before completing an initial version of this book in 1987. It was, therefore, consoling to have immediate and direct evidence of Desai’s work living on beyond his death, as happened one day in 1994 when I walked into an Indian carry-out restaurant in Paris and saw a colourful dance scene from Dharam-Veer playing on the conspicuously placed VCR. Those waiting in line stood transfixed before the screen, their faces radiating joy. Curious to know if Desai’s work had crossed the generations, I asked a young man in his twenties if he knew who had directed the film. ‘Manmohan Desai,’ came the answer without hesitation. Now, films, we know, come and go. Only the best remain in the public memory. Just as in the West each new generation has rediscovered Casablanca, It’s A Wonderful Life, or The Wizard Of Oz, so in India, there are examples—Shree 420, Mother India, Mughal-e-Azam and Sholay, among others—that have come to be classics. Some of Manmohan Desai’s films have joined that select group of films that never die, that remain etched on so many individual psyches that they become a part of a shared collective memory.

This book covers Manmohan Desai’s filmmaking from 1960 to 1988, but with special emphasis on what might be called the ‘Desai years,’ a time when Manmohan Desai was a major trendsetter and the biggest moneymaker in the film industry, a time when younger directors measured their own success against the Desai standard. In a fit of fevered activity between 1975 and 1985, Desai made nine films, all very successful, with Coolie and Amar Akbar Anthony reaching Platinum Jubilees, i.e., 75 weeks’ continued showing. Following the release of Gangaa Jamunaa Saraswathi in 1988, Desai left active directing. He continued his involvement with the film industry more indirectly through his son Ketan’s Allahrakha (1986), Toofan (1989) and Anmol (1993). But by that time, the ‘Desai years’ were over; unfortunately, so too was Manmohan Desai’s life one year later.

That an American teacher of English in Paris would write a book on Manmohan Desai’s cinema probably raises questions. In partial explanation and as an introduction, let me relate my discovery of Hindi popular cinema.

Generally speaking, I enjoy coming in contact with different cultures. I am also a fervent movie-goer. Living in Paris has allowed me to combine these two interests quite conveniently. Here, I have been able to roam new worlds from the comfort of motion picture theatre seats. With a selection of over 300 films per week, Paris offers journeys through time and space for relatively modest sums—with the added benefit of freedom from jet lag. During the l970s I saw films from China, Senegal, Mexico, the U.S.S.R., Japan, Poland, Italy, Iran, and many countries more. Yet I remained dissatisfied ... .

Among those who are attracted to cultures other than their own, it is common to find individual preferences in favour of one country over others. An affi

nity can spark curiosity or curiosity can reveal an affinity. Which comes first is often difficult to say. In my case, it is clear that India always interested me. Reading fiction and non-fiction had opened the doors to the country. I was disappointed then that Paris, even with its abundance of films, offered no cinematic trips there ... or so I thought.

In 1979 in one of the theatres in town, the first International Third World Film Festival was organized with an impressive selection of Indian films on the programme. I went off in high hopes of seeing what Indian cinema was about. I had only an inkling. In the Algerian film Omar Gatlato (by Merzak Allouache, 1976) the hero Omar watches Mangala El Bedouina (what I later learned was Aan, Mehboob Khan, 1952), and for several seconds we watch the film along with him. I wondered why the Algerians were permitted to see these delightful and colour-filled films while we in Paris—by many standards the film capital of the world—were not. Disappointingly, the Indian films did not arrive; African films were shown instead. However, the festival left me not only with images of the red soil of Burkina Faso but also with a teasing and intriguing printed list of the programmed Indian films. Synopses of Mother India, Pyaasa, Do Ankhen Barah Haath and others whetted my appetite. India obviously had a long cinematic heritage and boasted a wealth of films. It seemed all the stranger that we in Paris did not see them. At that point I could not have guessed that Indian films had already been playing regularly in town for some time.

There was no way to know about the Avron Palace or the Delta unless one happened to pass by or to learn about them through the immigrant communities’ grapevines. These two cinemas never had their films listed in the weekly film line-up magazines. One week, though, an exception was made. The name Amar Akbar Anthony appeared on the same footing as the new French, American, Japanese and Italian films released that week. Though I was eager to see the film, I could not help feeling a bit uneasy as I imagined possibly finding myself the only woman in the midst of an all-male audience at the Avron Palace. Pushing these doubts aside, I gave rein to my curiosity.

Manmohan Desai's Enchantment of the Mind

Manmohan Desai's Enchantment of the Mind